The Story of the Sacred Drum (adapted from Dr. Anton Treuer’s telling)

The mid 1800s was a time of extreme violence among Indian tribes and between those tribes and the United States government. In 1862, there was a major conflict between the Dakota and the US government. Two regiments were pulled away from the Civil War to completely evict the Dakota from Minnesota. During one government raid, a Dakota woman fled her encampment and was pursued by US soldiers. Eventually, she came to a lake. There, she heard the voice of the Great Spirit, who told her to go under water, and she would stay alive. She stayed under water for four days, as the soldiers continued to search for her. During that time, the Great Spirit gave her a dream. He said it was against his will for the Indian people to kill each other and he gave her a vision of a drum and said it would be a path to peace. She saw men seated around the drum and women surrounding them. Both were singing. This Great Spirit told her that the men around the drum should be men who killed Ojibwe, and that eventually, they would run out of men who had killed Ojibwe. After this vision, the spirit told her to leave the water, go to the soldiers’ camp, and break her fast. She went in, invisible to the soldiers, and ate in their mess tent. Then she returned to her people and relayed what had happened. Right away everyone believed her. They began to make the drum she described out of a washtub, but before it could be finished, the US soldiers came on another raid. When this happened, an Indian hit the washtub with a stick, and it immediately transformed into the drum. Upon hearing it, the soldiers fled.

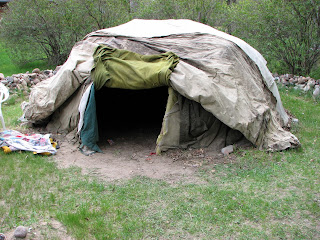

On Saturday, our class got to attend a sacred drum ceremony for the Thunder Bird Drum at the East Lake Community. The ceremony was hosted by drum chiefs David Niib Abid and Mushkoob Abid on property that used to belong to the East Lake Ojibwe but had been seized by the government and turned into a wildlife preserve. The location was an incredibly beautiful place—a ridge overlooking Rice Lake, covered with lilac and swarming with dragon flies.

The ceremony, which had actually started the previous evening, consisted of many segments of traditional songs. In each song, a spirit was represented by a specific person. During some songs, people simply stood and bent their knees at the beet of the drum. For other songs, men, women, or both danced around the drum. There were several tobacco offerings to the drum, and the pipe was passed around the room multiple times.

During one of the breaks, Mushkoob Abid told us about the history of the East Lake community—how they had been homeless for a long time after they were removed from their land and how now many of the tribe members were scattered. He also took us to Sandy Lake, which is known for the terrible tragedy that occurred there in 1850. In an attempt to relocate Michigan and Wisconsin Ojibwe tribes to free up farmland, the United States government announced that Indians would need to travel to Sandy Lake, Minnesota to receive the annuity goods it had promised. Although the government said that the goods would arrive no later than October 25, it didn’t deliver them until December 3, hoping that the Indians would decide not to return to their homelands. Meanwhile, about 400 Ojibwe perished from illness, hunger and exposure—either waiting for the food or trying to get home. Mushkoob also showed us the dam where the Mississippi flowes into the lake, a spot that was teeming with giant Buffalohead fish.

Over the course of the day, there were two feasts. We sat down to a long table with hundreds of dishes on it—ranging from wild rice and fresh fruit to fried chicken and cherry pie. It was a true feast—like something out of medieval times.

The evening ended with a giveaway dance. We exchanged gifts and joined classmates and East Lake members for several dances around the drum.

The mid 1800s was a time of extreme violence among Indian tribes and between those tribes and the United States government. In 1862, there was a major conflict between the Dakota and the US government. Two regiments were pulled away from the Civil War to completely evict the Dakota from Minnesota. During one government raid, a Dakota woman fled her encampment and was pursued by US soldiers. Eventually, she came to a lake. There, she heard the voice of the Great Spirit, who told her to go under water, and she would stay alive. She stayed under water for four days, as the soldiers continued to search for her. During that time, the Great Spirit gave her a dream. He said it was against his will for the Indian people to kill each other and he gave her a vision of a drum and said it would be a path to peace. She saw men seated around the drum and women surrounding them. Both were singing. This Great Spirit told her that the men around the drum should be men who killed Ojibwe, and that eventually, they would run out of men who had killed Ojibwe. After this vision, the spirit told her to leave the water, go to the soldiers’ camp, and break her fast. She went in, invisible to the soldiers, and ate in their mess tent. Then she returned to her people and relayed what had happened. Right away everyone believed her. They began to make the drum she described out of a washtub, but before it could be finished, the US soldiers came on another raid. When this happened, an Indian hit the washtub with a stick, and it immediately transformed into the drum. Upon hearing it, the soldiers fled.

On Saturday, our class got to attend a sacred drum ceremony for the Thunder Bird Drum at the East Lake Community. The ceremony was hosted by drum chiefs David Niib Abid and Mushkoob Abid on property that used to belong to the East Lake Ojibwe but had been seized by the government and turned into a wildlife preserve. The location was an incredibly beautiful place—a ridge overlooking Rice Lake, covered with lilac and swarming with dragon flies.

The ceremony, which had actually started the previous evening, consisted of many segments of traditional songs. In each song, a spirit was represented by a specific person. During some songs, people simply stood and bent their knees at the beet of the drum. For other songs, men, women, or both danced around the drum. There were several tobacco offerings to the drum, and the pipe was passed around the room multiple times.

During one of the breaks, Mushkoob Abid told us about the history of the East Lake community—how they had been homeless for a long time after they were removed from their land and how now many of the tribe members were scattered. He also took us to Sandy Lake, which is known for the terrible tragedy that occurred there in 1850. In an attempt to relocate Michigan and Wisconsin Ojibwe tribes to free up farmland, the United States government announced that Indians would need to travel to Sandy Lake, Minnesota to receive the annuity goods it had promised. Although the government said that the goods would arrive no later than October 25, it didn’t deliver them until December 3, hoping that the Indians would decide not to return to their homelands. Meanwhile, about 400 Ojibwe perished from illness, hunger and exposure—either waiting for the food or trying to get home. Mushkoob also showed us the dam where the Mississippi flowes into the lake, a spot that was teeming with giant Buffalohead fish.

Over the course of the day, there were two feasts. We sat down to a long table with hundreds of dishes on it—ranging from wild rice and fresh fruit to fried chicken and cherry pie. It was a true feast—like something out of medieval times.

The evening ended with a giveaway dance. We exchanged gifts and joined classmates and East Lake members for several dances around the drum.