The final days of our trip have been as hectic (and as educational) as the first ones. Though we got a little rest on Sunday, we also spent some time with Bob Shimmick, who talked to us about land use in Indian country. He critiqued Paul Bunyan mythology and the logging companies that have not only stripped reservation forests, but have often used coercive and deceptive methods to do so, like setting fires to be able to collect “dead and down” trees. He also discussed the conflicts that presently exist on reservations, where many of the lands allotted to Indians by the Dawes Act have been illegally taken and sold. On White Earth Reservation alone, 830,000 acres were stolen, and only 10,000 have been given back. Mr. Shimmick ended his talk with a challenge: “The problems existing in the world today cannot be solved by the level of thinking that created them.”

On Monday, we drove to Leech Lake Tribal College, where we met with interim president Dr. Ginny Carney. She spoke of the challenges of developing a post-secondary education institution within the native community. When she arrived as a teacher at the tribal college a few years after its founding, classes were being held in two abandoned churches and three condemned houses, and both teachers and students were frequently absent. Soon, under her guidance and the leadership of President Leah Carpenter, the college began hiring only teachers with masters degrees or those who would commit to earning them. Today, the college has two beautiful new buildings and offers accredited associates degrees in the arts and humanities, professional studies, and science. It offers one free course a year to reservation members 55 and older and provides education on issues like suicide, parenting, and AIDS. This year, it graduated a class of 40 students. But Dr. Carney said living out the mission to “provide a quality education grounded in Anishinabe values” is still an uphill battle, especially many of the students are discouraged from pursuing a higher education by friends and family.

We next listened to Bob Jourdain, an Ojibwe language instructor at the tribal college, who described his boarding school experience to us. When he was taken from his home and sent to a missionary run school in Carlisle Pennsylvania, he encountered the fate that the majority of Indian children from the 1800s to the mid 1970s faced. He described the emotional, physical, and sexual abuse that occurred in his school as well as the stripping of religion, culture, and language, which he was told was “the language of the devil, unfit for civilization.” Still, he credited that experience with teaching him how to read and study intensely and how to be tough, consistant, and to never give up. He went on to get a B.A. and masters degree in English and to work as a school counselor and grant writer. He now teaches at Leech Lake Tribal College, working to reverse the tragedy of language loss that has stemmed from the boarding school experience.

We spent the afternoon with Larry Aitken, a Professor of American Indian Studies at Itasca Community College. He described his teaching and learning experiences and shared with us his thoughts on knowledge, faith, pain, purpose, and poverty. “Money is good to have, but don’t make it your lifetime journey,” he warned us. “Being poor is when you do not have a belief in God.” He also asked is to give away the knowledge that we gain, especially the knowledge we gained on this trip.

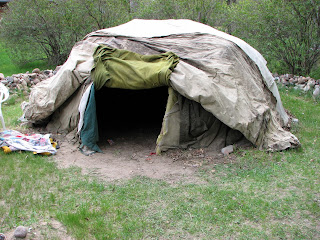

On Monday night, a group of fifteen of us had the opportunity to sleep in a teepee on the property of Will, an Ojibwe craftsman. Although teepees were not traditionally used by the Ojibwe (they preferred birch bark wigwams), we had a wonderful time sleeping not-quite-under-the-stars.

On Tuesday, we traveled to the White Earth Reservation, the largest reservation in Minnesota, with more than 20,000 enrolled members. White earth was like Leech Lake Reservation (and different from the Red Earth Reservation) in its “checkerboard” composition, a result of allotment and land theft. It was different from what we experienced at those two reservations in its progressive social and environmental justice programs as well as some of its political workings.

We toured the headquarters of the White Earth Land Recovery Project and Native Harvest, both founded by member Dr. Winona LaDuke (who you may remember as Ralph Nader’s running mate). The mission of the WELRP is to recover the original land base of the White Earth Nation and restore traditional practices of sound land stewardship, language fluency, community development, and spiritual and cultural heritage. We were taken to the foundation for a new wind turbine that will provide energy to the headquarters and sell energy back to the grid. We also got to see one of many solar energy panels that have been installed at White Earth houses to reduce heating costs. Native Harvest exists to provide economic opportunity through fair trade, employment, and marketing for the Anishinaabeg in the region. We had a few moments with Dr. LaDuke who talked about the challenges of relocalizing food and energy on White Earth. “Folks are conditioned to believe that things aren’t going to pan out for them,” she said. “That’s a mark of oppression. Our strategy is to do it.” We learned about the greenhouses that are providing fresh vegetables to local schools, ate lunch at the Native Harvest Restaurant, and toured Native Harvest’s wild rice processing facility. At Dr. LaDuke’s request, we spent some time picking up trash off the side of the road between the processing facility and the restaurant.

We spent Tuesday afternoon and evening with Paul Schultz, a White Earth elder, and his incredibly eloquent 10th-grade daughter, Lyra. Paul spoke about traditional healing, and Lyra explained the history and healing properties of the jingle dress, in which she performed a dance for us. Paul also talked about the sacredness of wild rice to the Anishinabe, as well as its health benefits. The rice is now in jeopardy because the University of Minnesota has genetically modified it. If the seed of rice from test plots is transported by wind or in bird droppings to native plots, truly wild rice could disappear.

Wednesday morning, we headed to White Earths new tribal government offices, where we met with Joe Lagarde, an activist and board member of WELRP. He talked about the political corruption that has plagued White Earth and described the new constitution that has recently been drafted (partly to curb that corruption). He also showed us a fascinating video, in which Dr. Claire Hendrickson presented historical documents and scientific evidence to support the Anishinabe oral tradition and the existence of indigenous Americans in the east 10,000-12,000 years ago (which opposes the popular theory that they migrated across the Bering Strait during the last ice age). After the video, we had the opportunity to meet the tribal chair, Erma Vizenor, who spoke briefly on the issue of the blood quantum. She pointed out that blood quantum was a policy instituted by the U.S. government to solve “the Indian problem” by ensuring that true “Indians” would no longer exist within several generations. The new constitution determines tribal membership by descendency, as opposed to blood quantum, which is different than the other five tribes in the band of Chippewa White Earth belongs to. “Why would we cooperate with blood quantum?” Dr. Vizenor said. “I don’t want to see the Minnesota Chippewa disband, but we need to be progressive. We will not cooperate in our own demise.”

Joe Lagarde treated us to lunch at one of White Earth’s Casinos, where a few of us made “contributions” to the slot machines and then swore off gambling for the rest of our lives. It was a slightly bizarre end to an amazing few weeks. Tomorrow, we head home to Pennsylvania. Twenty-five hours on the road will be good for thinking about how to integrate this experience into our lives. The Ojibwe believe that everything in life is circular. Perhaps this isn’t the end at all, but an encounter and a people we will revisit, if not in person, then in our writings, our conversations, and our dreams.

On Monday, we drove to Leech Lake Tribal College, where we met with interim president Dr. Ginny Carney. She spoke of the challenges of developing a post-secondary education institution within the native community. When she arrived as a teacher at the tribal college a few years after its founding, classes were being held in two abandoned churches and three condemned houses, and both teachers and students were frequently absent. Soon, under her guidance and the leadership of President Leah Carpenter, the college began hiring only teachers with masters degrees or those who would commit to earning them. Today, the college has two beautiful new buildings and offers accredited associates degrees in the arts and humanities, professional studies, and science. It offers one free course a year to reservation members 55 and older and provides education on issues like suicide, parenting, and AIDS. This year, it graduated a class of 40 students. But Dr. Carney said living out the mission to “provide a quality education grounded in Anishinabe values” is still an uphill battle, especially many of the students are discouraged from pursuing a higher education by friends and family.

We next listened to Bob Jourdain, an Ojibwe language instructor at the tribal college, who described his boarding school experience to us. When he was taken from his home and sent to a missionary run school in Carlisle Pennsylvania, he encountered the fate that the majority of Indian children from the 1800s to the mid 1970s faced. He described the emotional, physical, and sexual abuse that occurred in his school as well as the stripping of religion, culture, and language, which he was told was “the language of the devil, unfit for civilization.” Still, he credited that experience with teaching him how to read and study intensely and how to be tough, consistant, and to never give up. He went on to get a B.A. and masters degree in English and to work as a school counselor and grant writer. He now teaches at Leech Lake Tribal College, working to reverse the tragedy of language loss that has stemmed from the boarding school experience.

We spent the afternoon with Larry Aitken, a Professor of American Indian Studies at Itasca Community College. He described his teaching and learning experiences and shared with us his thoughts on knowledge, faith, pain, purpose, and poverty. “Money is good to have, but don’t make it your lifetime journey,” he warned us. “Being poor is when you do not have a belief in God.” He also asked is to give away the knowledge that we gain, especially the knowledge we gained on this trip.

On Monday night, a group of fifteen of us had the opportunity to sleep in a teepee on the property of Will, an Ojibwe craftsman. Although teepees were not traditionally used by the Ojibwe (they preferred birch bark wigwams), we had a wonderful time sleeping not-quite-under-the-stars.

On Tuesday, we traveled to the White Earth Reservation, the largest reservation in Minnesota, with more than 20,000 enrolled members. White earth was like Leech Lake Reservation (and different from the Red Earth Reservation) in its “checkerboard” composition, a result of allotment and land theft. It was different from what we experienced at those two reservations in its progressive social and environmental justice programs as well as some of its political workings.

We toured the headquarters of the White Earth Land Recovery Project and Native Harvest, both founded by member Dr. Winona LaDuke (who you may remember as Ralph Nader’s running mate). The mission of the WELRP is to recover the original land base of the White Earth Nation and restore traditional practices of sound land stewardship, language fluency, community development, and spiritual and cultural heritage. We were taken to the foundation for a new wind turbine that will provide energy to the headquarters and sell energy back to the grid. We also got to see one of many solar energy panels that have been installed at White Earth houses to reduce heating costs. Native Harvest exists to provide economic opportunity through fair trade, employment, and marketing for the Anishinaabeg in the region. We had a few moments with Dr. LaDuke who talked about the challenges of relocalizing food and energy on White Earth. “Folks are conditioned to believe that things aren’t going to pan out for them,” she said. “That’s a mark of oppression. Our strategy is to do it.” We learned about the greenhouses that are providing fresh vegetables to local schools, ate lunch at the Native Harvest Restaurant, and toured Native Harvest’s wild rice processing facility. At Dr. LaDuke’s request, we spent some time picking up trash off the side of the road between the processing facility and the restaurant.

We spent Tuesday afternoon and evening with Paul Schultz, a White Earth elder, and his incredibly eloquent 10th-grade daughter, Lyra. Paul spoke about traditional healing, and Lyra explained the history and healing properties of the jingle dress, in which she performed a dance for us. Paul also talked about the sacredness of wild rice to the Anishinabe, as well as its health benefits. The rice is now in jeopardy because the University of Minnesota has genetically modified it. If the seed of rice from test plots is transported by wind or in bird droppings to native plots, truly wild rice could disappear.

Wednesday morning, we headed to White Earths new tribal government offices, where we met with Joe Lagarde, an activist and board member of WELRP. He talked about the political corruption that has plagued White Earth and described the new constitution that has recently been drafted (partly to curb that corruption). He also showed us a fascinating video, in which Dr. Claire Hendrickson presented historical documents and scientific evidence to support the Anishinabe oral tradition and the existence of indigenous Americans in the east 10,000-12,000 years ago (which opposes the popular theory that they migrated across the Bering Strait during the last ice age). After the video, we had the opportunity to meet the tribal chair, Erma Vizenor, who spoke briefly on the issue of the blood quantum. She pointed out that blood quantum was a policy instituted by the U.S. government to solve “the Indian problem” by ensuring that true “Indians” would no longer exist within several generations. The new constitution determines tribal membership by descendency, as opposed to blood quantum, which is different than the other five tribes in the band of Chippewa White Earth belongs to. “Why would we cooperate with blood quantum?” Dr. Vizenor said. “I don’t want to see the Minnesota Chippewa disband, but we need to be progressive. We will not cooperate in our own demise.”

Joe Lagarde treated us to lunch at one of White Earth’s Casinos, where a few of us made “contributions” to the slot machines and then swore off gambling for the rest of our lives. It was a slightly bizarre end to an amazing few weeks. Tomorrow, we head home to Pennsylvania. Twenty-five hours on the road will be good for thinking about how to integrate this experience into our lives. The Ojibwe believe that everything in life is circular. Perhaps this isn’t the end at all, but an encounter and a people we will revisit, if not in person, then in our writings, our conversations, and our dreams.